In a recent interview, Pat Barker said Contemporary fiction is going through a “so what” moment, with very few novels generating a real sense of passion in readers and fiction, or the reading of fiction, was not in good health. I very much disagree with her and imagine she has spent too much time reading the likes of Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgård and other popular novelists and is unaware of or has been ignoring the many first-class works published by the ever-increasing number of small presses, who have continued to publish some excellent works this year.

She is not the only one. At the beginning of the year Tim Lott complained about modern literary fiction but failed to mention any author writing in a language other than English, where the most exciting literary fiction is being written.

In March I had a go at will Self (whom, surely, Tim Lott would not have liked) for saying the novel is doomed. As I pointed out, the novel is not doomed and certainly not the literary novel, particularly the literary novel originally written in languages other than English.

I wonder what Barker’s views were on Anna Burns’ Milkman, which won the Man Booker Prize this year. Some commentators claimed it was too difficult, a comment refuted by Sam Leith. I have read all the books in his list at the end of his article, except for the Cusk novel. I wonder how many Barker has read and what she thought of them. I think she needs to look around more and she will find some wonderful books out there. I certainly did.

As happens every year, I only read books from one country for a period during the early part of the year. This year the country was Catalonia. I read twenty books from twenty different Catalan authors, partially in sympathy with the Catalan independence movement, and enjoyed them all. Sadly, quite a few were not available in English.

Jaume Cabré‘s Jo confesso (Confessions), which is available in English and lots of other languages (I saw a Greek version at the London Book Fair) and Lluís-Anton Baulenas‘ Alfons XIV : un crim d’estat [Alfonso XIV: A Crime of State] (not available in English) were particular favourites but there were no disappointments. If you have not read any Catalan novels, I would strongly encourage you to do so. There are twenty-three Catalan authors on my website and quite a few have been translated into English.

I read 138 novels this year (last year 132). 43 were by women (35 last year, so a slight improvement). Apart from Catalonia, less well-represented countries include Basque, Bosnia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Greece, Greenland, Guatemala, Iran, Iraq, Latvia, Norway, Panama, Philippines, Poland, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Syria, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Of the countries that I read most, Catalonia was, of course, in first place followed by Argentina (nine, of which six were by César Aira), England (eight), Scotland (seven, six by Ali Smith), France (seven), Japan (six), Norway (six), China (six, four by Mo Yan), Croatia (four, three by Dubravka Ugrešić), Hungary (four, all by Miklós Szentkuthy), Italy (four) and Mexico (four).

Much of my reading, as in the past, was of books published by independent presses and, once again, they have produced a wonderful assortment of books for our enjoyment. Here are the ones whose books I read this year. If you are short of reading matter, you could no worse than browse their offerings: And Other Stories, Arcadia, Archipelago, Bellevue Literary Press, Cadmus, Canongate, Catapult, Contra Mundum, Dalkey Archive Press, Editions de Minuit, Fitzcarraldo, Granta, Grove Atlantic, Hoopoe, Inside the Castle, Istros, José Corti, Lilliput, Maclehose Press, New Directions, New Vessel Press, Nordisk, Oneworld Publications, Open Letter, Other Press, Parthian, Phébus, Peirene, Pushkin Press, Restless, Riverhead Press, Scribe Publications, Seren, Serpent’s Tail, Skyhorse, Tilted Axis, Two Dollar Radio, Urbanomic, Verba Mundi and Virago. A big thanks to all of them. My reading this year would have been much less interesting without them and also so would yours. I would also add thanks to the independent presses not mentioned here, all too often because I did not have time to get round to their books but would have done so if I had seriously curtailed my other activities.

I do make an effort to read only books that I am going to enjoy, so it is difficult to do a best-of list. There are plenty of those around, though, sadly, translated literature is generally not very well represented. As usual, Large-Hearted Boy has a comprehensive list. The TLS, for example, had a very comprehensive list of best books, particularly in non-fiction. However, there only six translated novels, three proposed by the admirable Lydia Davis and only two published this year and one published next year. Not surprisingly, we have to turn to World Literature Today for a comprehensive list of 2018’s translated highlights. Other lists of interest: Translating Women and The Best Reviewed Books of 2018: Literature in Translation. Best slightly quirky list: Best Books to Pretend to Have Read in 2018.

There were several firsts. I read and reviewed my first graphic novel: Hariton Pushwagner‘s Soft City, prompted by Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina being longlisted for the Man Booker. While I certainly enjoyed it, I think I much prefer words rather than pictures in my novels.

I read three collaborative novels this year definitely a new experience. These were Shatila Stories, a novel written by a group of refugees in the Shatila refugee camp, and two novels by Wu Ming, the Italian collective. All three were certainly interesting reads, though I am not entirely sure that this is the future of the novel.

I also read and reviewed, for the first time, on my site, a novel in which a character has a medical procedure to change sex: Rita Indiana‘s La mucama de Omicunlé (Tentacle). It is not the first transgender novel on my site: this one is. I suspect that we shall see more novels by and about transgender people.

Here is a rundown on the highlights of my reading this year. Apart from the Catalan works mentioned above, I particularly enjoyed the following:

I continue to make my way through the oeuvre of César Aira. I find his work to be particularly original and it must only be a matter of time till he wins the Nobel Prize, if it is ever awarded again. Quite a few have been published in English, mainly by New Directions.

Sticking to the Spanish-speaking world, Fernando Aramburu‘s Patria (Homeland) is a book you are likely to hear about next year. It concerns the ETA, the Basque terrorists/freedom fighters (depending on your point of view) and Spain’s attempt to come to terms with the issue. It has been hugely successful in Spain and has been translated into several languages. An eight-part TV series based on the book will be shown in Spain in 2020. It is coming out in English in March 2019.

Sticking with the Spanish-speaking world, I recently read Yolanda Oreamuno‘s La ruta de su evasión [The Route of Her Escape], a Costa Rican feminist novel from 1948 which I found excellent and I am surprised that it has not been translated into any other language.

The most controversial novel on my site this year was also, perhaps, from Latin America. Javier Pedro Zabala‘s The Mad Patagonian. I say perhaps because we do not know who Zabala is and where is from. We do know he is not Javier Pedro Zabala, as there is no such person.

The novel had a detailed biography of the author, which I was able to show was, at least, in part fake. The publishers replied in detail to my claims but admitted that the name, at least, was a pseudonym. While I enjoyed the book and said it was not a bad book, it was not as great as they claimed.

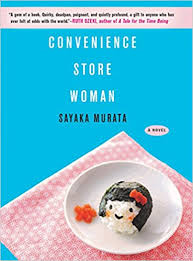

Moving to Asia I particularly enjoyed a couple of newly translated books from South-East Asia. Sayaka Murata‘s ンビニ人間 (Convenience Store Woman) is a Japanese novel about a young woman who takes a temporary job working in a convenience store and, eighteen years later, is still there. Despite an unpromising subject, it works very well, partially, perhaps, because it is based on the author’s own experiences. It is also one of quite a few novels I read this year with a fairly common theme – the person who does not fit in with societal norms. If I were a psychologist, I would say these people were often on the autistic spectrum but, as I am not a psychologist, I won’t.

The other one is from China: Yan Lianke‘s 日熄 (The Day the Sun Died). Quite a few of Yan Lianke’s novels have been translated into English and I hope to get round to the others some time. This one is about burials (which are not allowed in China – the issue also appears in Mo Yan‘s novels) and about a village (Yan Lianke’s own village – he is a character in the novel) whose inhabitants nearly all start sleepwalking.

The Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov currently lives in London, which may explain why four of his novels have been translated into English. His Jinlar Bazmi (The Devil’s Dance) appeared in English this year and a very fine novel it is. It is about the Uzbek writer Abdulla Qodiriy, who wrote the first full-length novel in Uzbek but who was executed in Stalin’s time. He mixes in Qodiriy’s story with the story of nineteenth century Uzbekistan and, in particular, the Great Game.

Sticking to the East but moving a bit West, specifically to Russia, Vladimir Sharov sadly died this year. I read two of his novels: Репетиции (Rehearsals) and До и во время (Before and During). Both books have something of a religious theme but don’t let this put you off. Both also jump between the present time and a historical period in Russia and make for fascinating reading.

Staying in Eastern Europe and, specifically, Hungary, I have now read all the books of Miklós Szentkuthy‘s Saint Orpheus’s Breviary series published in French and superb books they are, both anarchic and highly original. Sadly, Phébus, the French publisher, have stopped publishing them. Contra Mundum are planning to publish the entire series in English, which will be most welcome, but they seem to have been a bit quiet recently.

Moving further West. I have read more Norwegian books than I usually do. I read two books by Jon Fosse and two by Dag Solstad. While I was well aware of both, they are two of the many authors I should have read and have just not got round to. As regards Fosse, Lars Hertervig, the protagonist of his two Melancholia books and a very real person, is one of those mentioned above, someone who does not fit into into his society. Fosse’s portrait of insanity is masterful.

Two new Solstad novels came out in English this year, which means I still have to read a couple of his novels that appeared before. This year’s two – Armand V. (Armand V.) and T. Singer (T. Singer) – are both different, one quite political (Norway-US relations are key) as seen through the eyes of a Norwegian diplomat, with the novel essentially the footnotes to a novel and the other about an ordinary man who is, like most ordinary people, less ordinary. Both are very original and well worth reading. Nevertheless, they do not seem to have garnered the publicity they deserve.

Esther Kinsky clearly spent some time in Hackney, North London. Her Am Fluss (River) is a brilliantly evocative novel about the narrator’s time in Hackney, about the local river, the River Lea, and about other rivers. It is one of those novels that, on the face of it, might seem boring, but is so well written that it is a wonderful work that I cannot recommend too highly.

Paolo Cognetti‘s Le otto montagne (The Eight Mountains) has been translated into quite a few languages, including English but seems to have been more successful elsewhere than in the UK and US. It is a superb novel about the joys of mountaineering.

Closer to home, I enjoyed Jonathan Coe‘s Middle England, an anti-Brexit novel and a return to form for Coe.

This year I have been reading Ali Smith. It has been suggested that she is the only likely British candidate for the Nobel Prize and I could not disagree. She certainly one of the best if not the best current British novelist.

I have not really caught up with what is coming out next year – I like to be surprised – but will mention a few. Elfriede Jelinek‘s Die Kinder der Toten (The Children of the Dead) is, in theory, coming out from Yale University Press. At least that is what they told me a couple of years ago. However, there is no reference to it on their website. Wikipedia confirms this but cites me as the main source. So maybe it has been delayed again. I read it a while back and it is a brilliant book and a devastating attack on Austria.

Michel Houellebecq‘s new book Sérotonine is coming out in French on 4 January. Here is a link from the publisher’s website about it (in French). Ce roman sur les ravages d’un monde sans bonté, sans solidarité, aux mutations devenues incontrôlables, est aussi un roman sur le remords et le regret. [This novel of the ravages of a world without goodness, without solidarity, with changes which have become unchecked, is also a novel about remorse and regret.]. If I were paranoid, knowing of his dislike for the British, I would think he was having a go at Brexit.

As mentioned above Fernando Aramburu‘s Patria (Homeland) will be appearing in March.

The Comoros are not the first place you would look for to find a great novel but I really enjoyed Ali Zamir‘s Anguille sous Roche (it means Eel under Rock). Jacaranda will be publishing an English translation in 2019, entitled A Girl Called Eel. I can recommend it.

Vasily Grossman‘s Жизнь и судьба (Life and Fate) is one of the great World War II novels. He had previously published За правое дело [For a Just Cause] which had far more success in the Soviet Union which, unlike its successor, more or less toes the Soviet line. This book has been translated into French but not into English. Its original title was Stalingrad as it is about Grossman’s experiences in Stalingrad during the siege of that city. To make matters more complicated, he did publish a book called Stalingrad but it is a book of his reporting, i.e. non-fiction. To make matters even more complicated, the New York Review of Books will be publishing За правое дело in English under the title Stalingrad in 2019.

Various English-speaking women writers will be publishing new books in 2019. Margaret Atwood will be publishing a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale called The Testaments. Eleanor Catton will be publishing a book called Birnam Wood, set in a remote area of New Zealand where scores of ultra-rich foreigners are building fortress-like homes and stockpiling weapons in preparation for a coming global catastrophe. However, this was announced a couple of years ago and seems to have fallen off the radar like the Jelinek.

In Europe, Jeanette Winterson‘s Frankissstein will breathe new life into Mary Shelley’s horror story, grappling with issues of identity, technology and sexuality. Zadie Smith‘s new novel will be called Fraud and is inspired by real events from the 1830s to the 1870s England, a time when the streets of North West London still bordered fields and Kilburn’s ‘Shoot-Up Hill’ was named for a highwayman. Sticking to England but changing sex, I enjoyed Max Porter‘s Grief is the Thing With Feathers and shall look forward to his Lanny, coming out in 2019

Enrique Vila-Matas‘Mac y su contratiempo will be published in English by New Directions as Mac’s Problem and László Krasznahorkai‘s Baron Wenckeim’s Homecoming will be coming out in May.

Clarice Lispector is one of Brazil’s foremost writers. New Directions will be publishing her The Besieged City in 2019, which I am looking forward to.

Finally, will Vikram Seth‘s A Suitable Girl, a follow-up to his A Suitable Boy, appear in 2019? The answer is definitely maybe.

If you want to know more, The Literary Saloon has A list of lists of forthcoming books.

It just remains me for me to thank all of my fellow bloggers, from whom I learned much this year as every year. You will find a list of many of them on the right, further up.

I wish you happy reading in 2019.

Ismailov is a great author. I loved The Lake. here is my recap: https://wordsandpeace.com/2019/01/02/year-of-reading-2018-part-2-statistics/