This blog and the associated website are called The Modern Novel for a good reason, namely because they are about the modern novel. Since the website has been going, I have read very few non-fiction works and, inevitably, none of them has figured on my website. However, like every other intelligent reader in the Western world, I have been following the coverage of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Given that the issues he raised in his book seemed to overlap with many of my concerns but that, obviously, he was able to express them with far more intellectual rigour and, in particular, depth of economic knowledge and analysis than I could ever hope to do, I felt that it was time to read the book and mention it here. While I do enjoy reading fiction and probably spend far too much time doing so, fiction is not my only concern. I have strongly felt political views and am very much concerned with what is happening in the world today, particularly the huge disparity in wealth and income between the very rich and the rest of us, the tax avoidance manoeuvres of the very rich (both individuals and companies), the rise in food prices which is particularly hurting the poorer people in the developing world and the exploitation of workers that I am seeing in the UK (which may well be happening elsewhere) such as zero hour contracts. Piketty is keen to point out that he does not have a political agenda (though he does – see below), saying that he he reached the age of eighteen at around the time the Soviet Union broke up and therefore has no love for Communism. (I neither follow that argument nor accept his view on Communism – see below).

Piketty says The communist revolution did indeed take place, but in the most backward country in Europe, Russia, where the Industrial Revolution had scarcely begun, whereas the most advanced European countries explored other, social democratic avenues—fortunately for their citizens. This clearly shows that Piketty does have a political agenda – the standard anti-communist one. Firstly, of course, communism did not happen in Russia (or China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam, etc.). The fact they called it communism does not make it communist, just as the fact that the British Labour Party calling itself socialist makes it socialist. What happened in Russia (and China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam, etc.) was totalitarianism, using a state capitalist model, not a communist model. Except perhaps in a very few isolated cases and, maybe, though we do not know, in prehistoric times, communism has never existed anywhere, even slightly, on this planet. The fact that Piketty naively thinks it did exist and existed in Russia shows a political naivety? ignorance? which risks colouring our views of his views. Fortunately, much of his book is based on impartial economic analysis and it is that that is its strength, why it has had its success and why, for the most part, I enjoyed and learned a lot from the book. BTW, I am not now and never have been a communist, as I enjoy the fruits of capitalism too much, even if Senator Joe McCarthy would not have liked my political views.

I am not going to nor am I am competent to summarise all of Piketty’s ideas. Though the book is aimed at the intelligent layman, which, I hope, includes me, it does have economic ideas and statistical tables and discussions which I hope that I more or less grasped but which I am not sure that I am competent to accurately summarise. Having said that, I shall outline some of the main ones, by which I mean the ones that I found most interesting. I have always found it surprising that successive politicians and business people have pushed for ever increasing rates of growth. Surely, I have thought, this is not sustainable. Yet politicians trumpet how they have brought about an era of prosperity by having growth rates of 3-4%. Those of us who were around at the time of the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth and Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful (you can read a pdf of the whole book here), both of which I avidly read, have sometimes wondered why their ideas seem to have taken a back seat. Well, it seems that they might have been right all along. Many people think that growth ought to be at least 3 or 4 percent per year. As noted, both history and logic show this to be illusory, says Piketty, not because of his political views but because, historically, growth has been zero or close to it. 3-4% growth is neither normal nor sustainable. He goes on to say This level of growth [1.2%] cannot be achieved, however, unless new sources of energy are developed to replace hydrocarbons, which are rapidly being depleted. And justifies it.

When Margaret Thatcher came to power in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, they led a conservative revolution – I would call it a brutal conservative revolution because I do not have to be objective. Labour issues such as the air traffic controllers in the US and the miners in the UK typified their approach, with their fierce and unrelenting attack on the unions. When growth rates in both countries rose, they and their supporters claimed it was because of their policies. Not so says Piketty. In fact, neither the economic liberalization that began around 1980 nor the state interventionism that began in 1945 deserves such praise or blame. The UK and US would have caught up with the other industrial democracies whatever happened, he says, as it was all part of the economic cycle.

The most interesting approach is the one that shows that in the Western industrial countries, wealth had almost disappeared by the middle of the last century, as upheavals, particularly World War II, had wiped it out. At the national level, the capital/income ratio (capital stock divided by national income) had fallen by almost two thirds by 1945. What this means is that for the first part of the last century, wealth levels were high, owned, of course, by the rich, but the Depression and world wars severely cut them back. However, by now they are back at the same levels or even higher. You may be better off than your parents were but, unless you are on this list – and I am guessing that they don’t read this blog – you are many, many times less well off than these people. It had been thought, particularly by Simon Kuznets and his curve that we had been heading for a period of greater income equalty. Not a bit of it. Broadly speaking, it was the wars of the twentieth century that wiped away the past to create the illusion that capitalism had been structurally transformed. Capitalism has not changed. The rich are getting richer and, as Piketty says, this is a problem. Kuznets had been thought to have resolved this problem, with his very detailed analysis and study of the figures but as Pliketty now points out, he did not. Not even vaguely. Which mean that they – the economists, the conservatives, the Conservatives, him, him and him – not only got it wrong but are faced with a problem they are unwilling and unable to deal with.

But now the rich are very rich. Wealth is still extremely concentrated today: the upper decile own 60 percent of Europe’s wealth and more than 70 percent in the United States. And the poorer half of the population are as poor today as they were in the past, with barely 5 percent of total wealth in 2010, just as in 1910. Basically, all the middle class managed to get its hands on was a few crumbs: scarcely more than a third of Europe’s wealth and barely a quarter in the United States. This middle group has four times as many members as the top decile yet only one-half to one-third as much wealth. It is tempting to conclude that nothing has really changed: inequalities in the ownership of capital are still extreme. He qualifies this by saying that the few crumbs we (i.e. the not very rich middle class) got are not insignificant. However, the very rich may be even richer than we thought as, as we know, a lot of them are hiding their assets offshore and not paying all their taxes. And they are getting richer. The top thousandth enjoy a 6 percent rate of return on their wealth, while average global wealth grows at only 2 percent a year.

The big change he sees is To a large extent, we have gone from a society of rentiers to a society of managers, that is, from a society in which the top centile is dominated by rentiers (people who own enough capital to live on the annual income from their wealth) to a society in which the top of the income hierarchy, including the upper centile, consists mainly of highly paid individuals who live on income from labour. Their salaries have grown enormously – A stunning new phenomenon emerged in France in the 1990s: the very top salaries, and especially the pay packages awarded to the top executives of the largest companies and financial firms, reached astonishing heights — somewhat less astonishing in France, for the time being, than in the United States, but still, it would be wrong to neglect this new development. Interestingly, one of the reasons for this is because tax rates have dropped. In the 1950s-1970s, the UK and US led the way by having income tax rates of 80-90%. As a result, the top earners did not fight for increases, as they would all be eaten up in tax. When the tax rates were dropped, as a result of the conservative revolution and because the UK and US felt that they were not competing with Europe and Japan, the top earners asked for and got more. And this was not a good thing. In my view, there is absolutely no doubt that the increase of inequality in the United States contributed to the nation’s financial instability. Interestingly, the situation is worse (or better if you are super-rich) in the English-speaking countries. The upper centile’s share is nearly 20 percent in the United States, compared with 14–15 percent in Britain and Canada.

He has a solution. The ideal policy for avoiding an endless inegalitarian spiral and regaining control over the dynamics of accumulation would be a progressive global tax on capital. Contrary to some views, this would bring in a lot of revenue. The next point is important, and I want to insist on it: given the very high level of private wealth in Europe today, a progressive annual tax on wealth at modest rates could bring in significant revenue. Education would also help. By the same token, if the United States (or France) invested more heavily in high-quality professional training and advanced educational opportunities and allowed broader segments of the population to have access to them, this would surely be the most effective way of increasing wages at the low to medium end of the scale and decreasing the upper decile’s share of both wages and total income. All signs are that the Scandinavian countries, where wage inequality is more moderate than elsewhere, owe this result in large part to the fact that their educational system is relatively egalitarian and inclusive. He is highly critical of the fact that access to higher education is relatively costly in the US and UK. More efforts against tax avoidance are needed and he welcomes the US FATCA and castigates the EU for its feeble attempts in this area.

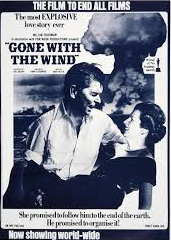

This is a stunningly simplified account of the points he makes. The book is nearly 700 pages long and full of incredible and fascinating details, tables, statistics, arguments and proposals. It is also a fascinating historical review and a literary one. Literary one? Piketty makes numerous references to books, film and TV (Mad Men!) in his book but the two authors who are referred to most are Jane Austen and Honoré de Balzac, who illustrate very well how the bourgeoisie lived, spent, earned and sought out money. He clearly know his Père Goriot and his Sense and Sensibility.

I do urge you to read this book as it looks likely to be be one of the most important books about our world to appear in recent years and even if, like me, you have no economics training, you should be able to get through most of it. However, it does require close study so do not think that you will read it one evening after work. It has taken me five days, reading it, thinking about it, discussing it with my family, checking some of his facts, but five days I consider very well spent and I feel much more knowledgeable than I did before reading it. Indeed, I expect that I will probably reread it in a year or so. I think that I may leave non-fiction for a while though, I must say, I am tempted by The Vagenda. Obviously, because financial and economics statistics generally do not differentiate by sex, Piketty does not discuss gender issues. However, I expect that most of the very rich are men and most of those that have suffered and continue to suffer because the rich have taken all the resources are women. Maybe someone could write a book on that.

This week’s Economist (pages 12 and 67) has a predictable take on Piketty’s Capital. We were expecting it but nevertheless found it entertaining.

Thanks for the references. I shall certainly look them up.